Although ARM was recently acquired by SoftBank, technology knows no borders, so it's still important to learn ARM-related knowledge. Looking at the ARM instruction set now feels quite familiar, as I took an ARM course in university and did many experiments. At the time, I felt I did a decent job of the course. Although I initially thought it wouldn't be very useful, it has now come in handy! However, I've forgotten most of what I learned before, so I have to pick it up again. The ARM instruction set is a reduced instruction set, as the name suggests, it has fewer instructions than more complex instruction sets. Of course, the ARM instruction set discussed in this article is just the tip of the iceberg, but it's still fundamental. You can start reading assembly language in Hopper now. Practice makes perfect; the more you read, the more you'll naturally learn.

I. ARM Instructions in Hopper

ARM processors need little introduction; due to their low power consumption, they are the primary architecture processors used in most mobile devices. Of course, Android phones and iPhones, being mobile devices, also use ARM architecture processors. If you want to gain a deeper understanding of the iOS system and your applications, then understanding the ARM instruction set is essential; the ARM instruction set can be considered the foundation for iOS reverse engineering.

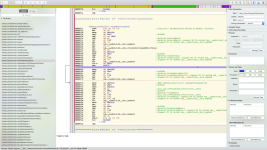

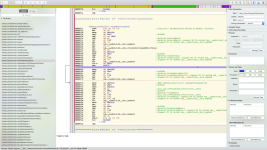

When you use Hopper to decompile, it's full of ARM instructions, which is really satisfying to look at. Below is a Hopper interface of MobileNote.app . You can see all the ARM instructions in the main window. If you don't understand ARM instructions, how can you analyze them, right? Therefore, understanding ARM instructions is fundamental to iOS reverse engineering. This blog post will summarize the basic instructions of the ARM instruction set.

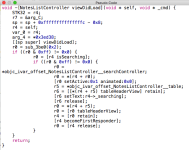

Hopper is a very powerful tool. With Hopper, you can modify ARM instructions and generate new executable files. Of course, Hopper's powerful features can also help you better understand the business logic of ARM assembly language. Hopper will generate relevant logic diagrams based on the ARM assembly, as shown below. From the logic diagram below, you can clearly see the relevant ARM assembly instruction logic. Red lines indicate jumps when conditions are false, while blue lines indicate jumps when conditions are true .

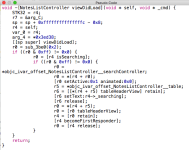

Hopper is powerful enough to generate corresponding pseudocode from ARM assembly language. If you find ARM instructions difficult to understand, then pseudocode will be much easier for you. Below is the pseudocode generated by Hopper based on ARM instructions.

We seem to have gone a bit off-topic. Today's topic is the ARM instruction set, so we won't go into too much detail about Hopper.

II. Overview of the ARM Instruction Set

ARM instructions primarily operate on registers, the stack, and memory. Registers reside within the CPU, are few in number, and operate quickly; most instructions in the ARM instruction set manipulate registers. However, some instructions operate on the stack and memory. Instructions for manipulating the stack, registers, and memory will be described below.

1. Stack operations – push and pop

Let's start with a simple discussion of the concept of a stack. Simply put, a stack is a data structure that exhibits LIFO (Last in First Out) characteristics. In ARM architecture, a stack refers to a memory area with stack data structure features. The stack is primarily used to temporarily store values from registers. For example, if register R0 is currently in use, but a higher-priority function needs to use R0, the value of R0 is pushed onto the stack for temporary storage. Then, once the higher-priority function has finished using R0, its previous value is popped back from the stack. Stack operations are typically performed during function calls.

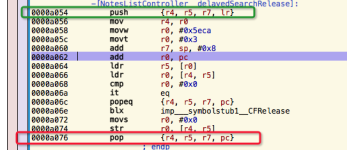

The commands for stack operations are push and pop , which usually appear in pairs. At the beginning of a function, the values in the registers that the function will use during execution are pushed onto the stack, and at the end of the function, the values previously pushed onto the stack are popped back into the corresponding registers.

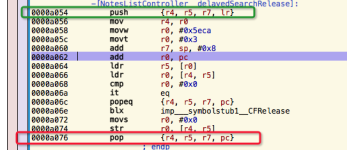

Below is an example of the usage of `push` and `pop`. Before the function below begins execution, registers r4, r5, r7, and lr, which the function will use , are pushed onto the stack using the `push` command . `lr` is the address the function will return from after execution . After the function finishes execution, the values pushed onto the stack before execution are popped back into the corresponding registers. It's important to note that the value in the `lr` register is popped into the `pc` ( Program Counter ) register after the function ends. The `pc` register stores the address of the command to be executed . This way, the function will return to the previously executed address and continue execution.

2. Flag bits in the PC register

Here we take 32-bit instructions as an example. The last four bits in the PC register are flag bits, and bits 28-31 correspond to V (overflow), C (carry), Z (zero), and N (negative) , respectively. We will now explain the states represented by these four symbols.

3. Command operators

Below are commonly used arithmetic operations in the ARM instruction set:

(1) Addition operation

(2) Subtraction operation

In the ARM instruction set, there are two types of multiplication instructions: the first is MUL, and the second is MLA with accumulation. Neither of these instructions is complicated to use.

(4) Logical operations

Logical operations are easier to understand, as they are similar to the logical operations we use in programming, mainly consisting of AND, OR, NOT, and XOR operations.

4. Loading and storing registers

Sometimes we need to load data from memory into registers for manipulation, or store data from register operations into memory. In these cases, we use the commands for loading and storing registers. These commands are summarized below.

(1) Transmitting single data

LDR{condition} Rd, <address> ; Loads the data at the specified address into the Rd register.

STR{condition} Rd, <address> ; Stores the value in register Rd into the memory at <address>.

LDR{condition}B Rd, <address> ; Loads the lower 8 bits of the value corresponding to the memory address into the register Rd.

STR{condition}B Rd, <address> ; Stores the last 8 bits of register Rd into the memory address.

(2) Transmit two data at once

(3) Block data access

(4) Single Data Exchange: SWP

The SWP command is used to swap values between registers and memory. Below is the SWP command format:

SWP{condition}{B} Rd, Rm, [Rn]

The above command loads the data from the memory address pointed to by Rn into Rd, and then stores the value in register Rm into the memory area pointed to by that memory address. If Rd = Rm, then the value in the memory pointed to by Rn will be swapped with Rd. Adding a conditional suffix indicates that the operation will be performed when that condition is met; the suffix B operates on the lower 8 bits.

5. Comparison, branching, and conditional instructions

Branching and conditional instructions are indispensable in programming, frequently used when handling specific business logic. A branch, simply put, is a jump, while combining branching and conditional instructions allows for a specific jump after certain conditions are met. The following will summarize commonly used branching and conditional instructions in the ARM instruction set, more precisely, conditional suffixes.

(1) Comparison instructions

The comparison instructions used in the ARM instruction set are CMN, CMP, TEQ, and TST. It's important to note that CMN and CMP are arithmetic instructions , while TEQ and TST are logical instructions . Comparison instructions always set flags ( N, Z, C, V ) after execution, because the conditional suffix determines whether the comparison result meets the set flags. A detailed list of conditional suffixes is provided below. Conditional suffixes can also be added after comparison commands.

The most commonly used branch instructions are B, BL, and BX.

(3) Conditional suffix

The branching commands mentioned above, combined with conditional suffixes, are essential for their powerful functionality. This section explains our conditional suffixes. Conditional suffixes cannot be used alone; they must be used in conjunction with other commands to perform operations based on the condition's result. Below are all the conditional suffixes. Whether a condition is true or false is determined by the four flags: N, Z, and C. When comparing numerical values, we set corresponding flags. We can then use these flags to determine if the condition is true or false. N, Z, and C are the flags we mentioned earlier: Z (whether it's zero), C (whether there's a carry), N (whether it's negative), and V (whether there's an overflow) .

6. Shift operations (LSL, ASL, LSR, ASR, ROR, RRX)

Shift operations are not used as standalone commands in the ARM instruction set; they are a field in the instruction format. The following sections will introduce various shift operations. If you have previously studied " Digital Circuits ," you will certainly be familiar with these shift operations.

(1) LSL ---- Logical Shift Left and ASL ---- Arithmetic Shift Left

Logical left shift and arithmetic left shift operate in the same way: shifting the operand to the left, filling the lower bits with zeros, and discarding the higher bits being removed. Let's look at an example to see how LSL or ASL works.

(2) LSR ---- Logical Shift Right

Logical right shift and logical left shift are relative operations. Logical right shift simply means shifting bits to the right and filling the left side with zeros. Its usage is similar to LSL, so I won't go into detail here.

(3) ASR ---- Arithmetic Shift Right

ASR is similar to LSR, the only difference being that LSR pads the high-order bits with zeros, while ASR pads the high-order bits with the sign bit. If the sign bit is 1, it is padded with 1; if the sign bit is 0, it is padded with zeros.

(4) ROR ---- Rotate Right

Circular right shift, as the name suggests, involves moving to the right in a circular manner, filling the positions removed on the right with higher positions.

That's all for today's blog post, as space is limited. The commands above are some basic ones. Other floating-point instructions, such as ABS (absolute value), ACS (arccosine), and ASN (arcsine), will not be discussed in detail here; readers can explore those on their own.

I. ARM Instructions in Hopper

ARM processors need little introduction; due to their low power consumption, they are the primary architecture processors used in most mobile devices. Of course, Android phones and iPhones, being mobile devices, also use ARM architecture processors. If you want to gain a deeper understanding of the iOS system and your applications, then understanding the ARM instruction set is essential; the ARM instruction set can be considered the foundation for iOS reverse engineering.

When you use Hopper to decompile, it's full of ARM instructions, which is really satisfying to look at. Below is a Hopper interface of MobileNote.app . You can see all the ARM instructions in the main window. If you don't understand ARM instructions, how can you analyze them, right? Therefore, understanding ARM instructions is fundamental to iOS reverse engineering. This blog post will summarize the basic instructions of the ARM instruction set.

Hopper is a very powerful tool. With Hopper, you can modify ARM instructions and generate new executable files. Of course, Hopper's powerful features can also help you better understand the business logic of ARM assembly language. Hopper will generate relevant logic diagrams based on the ARM assembly, as shown below. From the logic diagram below, you can clearly see the relevant ARM assembly instruction logic. Red lines indicate jumps when conditions are false, while blue lines indicate jumps when conditions are true .

Hopper is powerful enough to generate corresponding pseudocode from ARM assembly language. If you find ARM instructions difficult to understand, then pseudocode will be much easier for you. Below is the pseudocode generated by Hopper based on ARM instructions.

We seem to have gone a bit off-topic. Today's topic is the ARM instruction set, so we won't go into too much detail about Hopper.

II. Overview of the ARM Instruction Set

ARM instructions primarily operate on registers, the stack, and memory. Registers reside within the CPU, are few in number, and operate quickly; most instructions in the ARM instruction set manipulate registers. However, some instructions operate on the stack and memory. Instructions for manipulating the stack, registers, and memory will be described below.

1. Stack operations – push and pop

Let's start with a simple discussion of the concept of a stack. Simply put, a stack is a data structure that exhibits LIFO (Last in First Out) characteristics. In ARM architecture, a stack refers to a memory area with stack data structure features. The stack is primarily used to temporarily store values from registers. For example, if register R0 is currently in use, but a higher-priority function needs to use R0, the value of R0 is pushed onto the stack for temporary storage. Then, once the higher-priority function has finished using R0, its previous value is popped back from the stack. Stack operations are typically performed during function calls.

The commands for stack operations are push and pop , which usually appear in pairs. At the beginning of a function, the values in the registers that the function will use during execution are pushed onto the stack, and at the end of the function, the values previously pushed onto the stack are popped back into the corresponding registers.

Below is an example of the usage of `push` and `pop`. Before the function below begins execution, registers r4, r5, r7, and lr, which the function will use , are pushed onto the stack using the `push` command . `lr` is the address the function will return from after execution . After the function finishes execution, the values pushed onto the stack before execution are popped back into the corresponding registers. It's important to note that the value in the `lr` register is popped into the `pc` ( Program Counter ) register after the function ends. The `pc` register stores the address of the command to be executed . This way, the function will return to the previously executed address and continue execution.

2. Flag bits in the PC register

Here we take 32-bit instructions as an example. The last four bits in the PC register are flag bits, and bits 28-31 correspond to V (overflow), C (carry), Z (zero), and N (negative) , respectively. We will now explain the states represented by these four symbols.

- N ( Negative ): Set if the result is negative.

- Z ( Zero ): Set if the result is zero.

- C ( Carry ): Set the bit if there is a carry.

- V ( Overflow ): Set when an overflow occurs.

3. Command operators

Below are commonly used arithmetic operations in the ARM instruction set:

(1) Addition operation

- ADD R0, R1, R2 ; R0 = R1 + R2

- The command above is quite simple; it adds two values together.

- ADC R0, R1, R2 ; R0 = R1 + R2 + C (Carry)

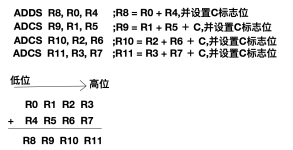

- For addition with carry, the ADC adds the two operands together and places the result in the destination register. The ADC uses the C-carry flag , allowing it to perform additions larger than 32 bits. Below is the assembly code for adding a 128-bit number.

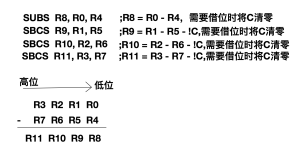

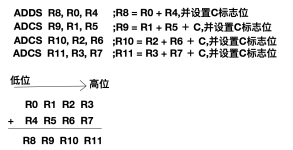

- We are now going to perform an addition operation on a 128-bit number. Since we are using 32-bit registers, we need four registers (128 / 32 = 4) to store a 128-bit number. Let's assume registers R0, R1, R2, and R3 store the first number from low to high, while R4, R5, R6, and R7 store the second number. Below are the ARM assembly instructions for adding two 128-bit numbers. We will store the result in registers R8, R9, R10, and R11. First, we add the least significant bits of the two numbers and set the C flag ( ADDS R8, R0, R4 ). Then, we proceed to the next bit operation, adding the values in R1 and R5, adding the carry from the previous operation, and then setting the flag again, and so on. In this way, our final value is stored in registers R8-R11 .

(2) Subtraction operation

- SUB R0, R1, R2 ; R0 = R1 - R2

- The naming convention is quite simple: subtract the value in register R2 from the value in register R1, and then store the result in register R0.

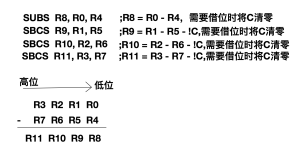

- SBC R0, R1, R2 ; R0 = R1 - R2 - !C

- Subtraction with borrow: If our current register is 32-bit, and we are subtracting two 64-bit values, we need to use the SBC borrow operation. This is because when two values are subtracted, if a borrow is needed, the C flag will be cleared. Therefore, the C flag needs to be inverted before performing the SBC operation. Below, we will use the subtraction of 128-bit values as an example. This example is similar to the ADC command mentioned above, so we will not elaborate further.

- RSB R0, R1, R2 ; R0 = R2 - R1

- Reverse subtraction

- RSC R0, R1, R2 ; R0 = R2 - R1 - !C

- Reverse subtraction with borrow: The two commands above are similar to the SUB and SBC commands, all performing subtraction operations, but the order of operand calculation is different.

In the ARM instruction set, there are two types of multiplication instructions: the first is MUL, and the second is MLA with accumulation. Neither of these instructions is complicated to use.

- MUL: Multiplication instruction MUL{condition}{S} R0, R1, R2 ;R0 = R1 * R2

- MLA: Multiply-Accumulate instruction MLA{condition}{S} R0, R1, R2, R3 ; R0 = R1 * R2 + R3

(4) Logical operations

Logical operations are easier to understand, as they are similar to the logical operations we use in programming, mainly consisting of AND, OR, NOT, and XOR operations.

- AND R0, R1, R2 ; R0 = R1 & R2

- AND operation: 1 & 1 = 1, 1 & 0 = 1, 0 & 1 = 1, 0 & 0 = 0 ;

- ORR R0, R1, R2 ; R0 = R1 | R2

- OR operation: 1 | 1 = 1, 1 | 0 = 1, 0 | 1 = 1, 0 | 0 = 0 ;

- EOR R0, R1, R2 ; R0 = R1 ^ R2

- XOR: 1 ^ 1 = 1, 1 ^ 0 = 0, 0 ^ 1 = 0, 0 ^ 0 = 1 ;

- BIC R0, R1, R2 ; R0 = R1 &~ R2

- The bit clear instruction inverts R2 and then performs a bitwise AND operation with R1. R1 & (~R2)

- Clear the last four bits of R0: BIC R0, R0,#0x0F

- MOV R0, R1 ;R0 = R1

- The assignment operation assigns the value of R1 to R0.

- MVN R0, R1 ;R0 = ~R1

- The bitwise NOT operation inverts each bit of R1 and then assigns it to R0.

4. Loading and storing registers

Sometimes we need to load data from memory into registers for manipulation, or store data from register operations into memory. In these cases, we use the commands for loading and storing registers. These commands are summarized below.

(1) Transmitting single data

LDR{condition} Rd, <address> ; Loads the data at the specified address into the Rd register.

STR{condition} Rd, <address> ; Stores the value in register Rd into the memory at <address>.

LDR{condition}B Rd, <address> ; Loads the lower 8 bits of the value corresponding to the memory address into the register Rd.

STR{condition}B Rd, <address> ; Stores the last 8 bits of register Rd into the memory address.

- LDR (Load Register): Retrieves data from memory and loads it into a register.

- LDR Rt, [Rn], #offset ;Rt = *Rn; Rn = Rn + offset

- LDR Rt, [Rn, #offset]! ; Rt = *(Rn + offset); Rn = Rn + offset

- STR (Store Register): Stores the data in the register into memory.

- STR Rt, [Rn], #offset ;*Rn = Rt; Rn = Rn + offset

- STR Rt, [Rn, #offset]! ;*(Rn + offset) = Rt; Rn = Rn + offset (address write-back)

(2) Transmit two data at once

- LDRD (Load Register Double): Fills two registers at once.

- LDRD R4, R5, [R6, #offset] ;R4 = *(R6 + offset); R5 = *(R6 + offset + 4)

- STRD (Store Register Double): Stores two values into memory at once.

- STRD R4, R5, [R6, #offset] ;*(R6 + offset) = R4; *(R6 + offset + 4) = R5

(3) Block data access

- LDM (Load Multiple): Loads a block of data from memory into a register (reg list).

- STM (Store Multiple) : Loads block data from memory into registers.

- Both LDM and STM block memory operations have a suffix, and the following are the four conditions. We assume that the value stored in register R0 below is 0 (R0 = 6).

- IA (Increment After) : Values are incremented after transmission.

- For example: LDMIA R0, {R1 - R3} ; R1 = 6, R2 = 7, R3 = 8

- IB (Increment Before) : Value added before transmission

- For example: LDMIB R0, {R1 - R3} ; R1 = 7, R2 = 8, R3 = 9

- DA (Decrement After) : The value decreased after transmission.

- For example: LDMDA R0, {R1 - R3} ; R1 = 6, R2 = 5, R3 = 4

- DB (Decrement Before) : Value reduced before transmission

- For example: LDMDB R0, {R1 - R3} ; R1 = 5, R2 = 4, R3 = 3

- IA (Increment After) : Values are incremented after transmission.

(4) Single Data Exchange: SWP

The SWP command is used to swap values between registers and memory. Below is the SWP command format:

SWP{condition}{B} Rd, Rm, [Rn]

The above command loads the data from the memory address pointed to by Rn into Rd, and then stores the value in register Rm into the memory area pointed to by that memory address. If Rd = Rm, then the value in the memory pointed to by Rn will be swapped with Rd. Adding a conditional suffix indicates that the operation will be performed when that condition is met; the suffix B operates on the lower 8 bits.

5. Comparison, branching, and conditional instructions

Branching and conditional instructions are indispensable in programming, frequently used when handling specific business logic. A branch, simply put, is a jump, while combining branching and conditional instructions allows for a specific jump after certain conditions are met. The following will summarize commonly used branching and conditional instructions in the ARM instruction set, more precisely, conditional suffixes.

(1) Comparison instructions

The comparison instructions used in the ARM instruction set are CMN, CMP, TEQ, and TST. It's important to note that CMN and CMP are arithmetic instructions , while TEQ and TST are logical instructions . Comparison instructions always set flags ( N, Z, C, V ) after execution, because the conditional suffix determines whether the comparison result meets the set flags. A detailed list of conditional suffixes is provided below. Conditional suffixes can also be added after comparison commands.

- CMN (Compare Negative) – Compares negative values. CMN is the same as CMP, but it allows you to compare negative values.

- CMN R0, R1 ;Status = R0 - R1

- CMP (Compare)– The reason CMP and CMN instructions are called arithmetic instructions is because they perform subtraction on their operands and set corresponding flags, but do not record the result. CMN and CMP perform arithmetic subtraction, so they affect the C-Carry flag.

- CMP R0, R1 ;Status = R0 - R1

- TEQ (Test Equivalence)– Tests equivalence. TEQ performs an XOR (Exclusive OR) operation on the operands to determine if two operands are the same. Because TEQ performs an XOR operation, it does not affect the Carry flag.

- TEQ R0, R1 ;Status = R0 EOR R1

- TST (Test bits) ---- Test bits are used to check if specific bits are set. The TST hit command performs a bitwise AND operation on two operands and stores the result in a flag. TST can be used to test the specific values of certain bits in a register.

- TST R0, R1 ;Status = R0 AND R1

The most commonly used branch instructions are B, BL, and BX.

- B Label ; This instruction sets the PC to a Label, and the PC points to the next instruction to be executed. Therefore , after B Label is executed, the system will jump to the Label to execute the next command.

- `BL Label` ; This instruction sets `LR` to `PC - 4`, and then sets `PC` to `Label`. When executing the `BL Label` command, `PC` stores the current `BL` command, and `PC - 4` is the address of the previous instruction. Assigning `PC - 4` to `LR` records the return address after the jump instruction is executed. If conditions are added to `BL`, then `BL{condition}` can loop.

- BX Rd ; This instruction assigns Rd to PC and then switches the instruction set (e.g., from ARM to Thumb ).

(3) Conditional suffix

The branching commands mentioned above, combined with conditional suffixes, are essential for their powerful functionality. This section explains our conditional suffixes. Conditional suffixes cannot be used alone; they must be used in conjunction with other commands to perform operations based on the condition's result. Below are all the conditional suffixes. Whether a condition is true or false is determined by the four flags: N, Z, and C. When comparing numerical values, we set corresponding flags. We can then use these flags to determine if the condition is true or false. N, Z, and C are the flags we mentioned earlier: Z (whether it's zero), C (whether there's a carry), N (whether it's negative), and V (whether there's an overflow) .

- EQ : Equal (Z = 1)

- NE : Not Equal (Z = 0)

- CS : Carry Set with carry (C = 1)

- HS: (unsigned Higher Or Same) 同CS (C = 1)

- CC : (Carry Clear) No carry (C = 0)

- LO: (unsigned Lower) 同CC (C = 0)

- MI : (Minus) The result is less than 0 (N = 1)

- PL : (Plus) Result greater than or equal to 0 (N = 0)

- VS : (oVerflow Set) Overflow (V = 1)

- VC : (oVerflow Clear) No overflow (V = 0)

- HI : (unsigned Higher) Unsigned comparison, greater than (C = 1 & Z = 0)

- LS : (unsigned Lower or Same) Unsigned comparison, less than or equal to (C = 0 & Z = 1)

- GE : (signed Greater than or Equal) Signed comparison, greater than or equal to (N = V)

- LT : (signed Less Than) Signed comparison, less than (N != V)

- GT : (signed Greater Than) Signed comparison, greater than (Z = 0 & N = V)

- LE : (signed Less Than or Equal) Signed comparison, less than or equal to (Z = 1 | N != V)

- AL : (Always) Unconditional, default value

- NV : (Never) Never execute

6. Shift operations (LSL, ASL, LSR, ASR, ROR, RRX)

Shift operations are not used as standalone commands in the ARM instruction set; they are a field in the instruction format. The following sections will introduce various shift operations. If you have previously studied " Digital Circuits ," you will certainly be familiar with these shift operations.

(1) LSL ---- Logical Shift Left and ASL ---- Arithmetic Shift Left

Logical left shift and arithmetic left shift operate in the same way: shifting the operand to the left, filling the lower bits with zeros, and discarding the higher bits being removed. Let's look at an example to see how LSL or ASL works.

The above command stores 5 in register R0 (R0 = 5), then logically shifts R0 left by 2 bits and transfers the result to register R1. The binary value of decimal 5 is 0101, so logically shifting it left by 2 bits gives 0001_0100, which is 20 in decimal. Essentially, each logical left shift is equivalent to multiplying the original value by 2; logically shifting 5 left by 2 bits is 5 x 2^2 = 20. Below is a diagram illustrating this operation.MOV R0, #5

MOV R1, R0, LSL #2

(2) LSR ---- Logical Shift Right

Logical right shift and logical left shift are relative operations. Logical right shift simply means shifting bits to the right and filling the left side with zeros. Its usage is similar to LSL, so I won't go into detail here.

(3) ASR ---- Arithmetic Shift Right

ASR is similar to LSR, the only difference being that LSR pads the high-order bits with zeros, while ASR pads the high-order bits with the sign bit. If the sign bit is 1, it is padded with 1; if the sign bit is 0, it is padded with zeros.

(4) ROR ---- Rotate Right

Circular right shift, as the name suggests, involves moving to the right in a circular manner, filling the positions removed on the right with higher positions.

That's all for today's blog post, as space is limited. The commands above are some basic ones. Other floating-point instructions, such as ABS (absolute value), ACS (arccosine), and ASN (arcsine), will not be discussed in detail here; readers can explore those on their own.